Justice Eats The World, Part 2

The Invisible Hand of Egalitarianism

Last week we discussed both how justice eats the world as a counter to the winner-take-all effects of software and because there are status benefits to being more egalitarian.

We looked at how labor marketplaces (and dating apps) turn local software marketplaces into global ones which both exacerbates disparities as well as codifying disparities in the first place — pre-marketplaces we couldn’t quantify outcomes as easily.

While we discussed examples, they were mostly at the individual level. In this piece we’re going to discuss how justice eats the world at a more systemic level. In other words, I will be describing how the invisible hand of egalitarianism works.

Spoiler: By promising people more status.

How Status got Inverted

Zooming out: Prior to Christianity, value system and myths were all oriented around strength, excellence, and achievement. Christianity flipped morality upside down: “The first shall be last, last shall be first.“ Nietzsche saw this flipping and lamented it.

In other words, Christianity reordered values in western society from veneration of the strong to veneration of the weak — from condemnation of the weak to commendation of the strong. “The Meek shall inherit the earth”

Then Darwin came along and killed god. And so we were left to invent our own value systems. Which was hard. So instead of starting from scratch, we repurposed our existing Christian ethics under new names like “egalitarianism,“ "equality,” "Marxism," "Communism," “social justice,” even “atheism"!

To provide more historical context: The introduction of capitalism was a big deal. It reoriented who became high status (e.g. merchants) and who didn't (e.g. intellectuals). Those who lost status felt resentful. Socialism catered to that resentment by promising status back to those with low-status. This is important because as we discussed before: the thing people care most about is status, or having a high reputation among the people they care about.

Christianity promised the meek that they'd go to heaven — unlike rich people. In contrast, socialism promised the goods here on Earth. This is why it became so popular.

Socialism is also a highly effective political strategy because of one key defining quality: it attracts people who are loyal. Say what you want about how bad communism was (and it was truly horrible), but one thing is for sure: it breeds loyalty. The USSR was loyal. China is loyal. In contrast, rich Americans are not loyal — they simply have too many other good options available to them. As they say, “people are only as loyal as their options.”

The main reason socialism didn't work in the west is that its people became too rich for socialism’s value props to sell. The west believed too much in The American Dream — that they too could get rich if they were talented and worked hard. From an expected value perspective, it made much more sense to believe in capitalism than socialism.

It’s worth noting that this is why economic growth is so important. When we're not growing, the world becomes zero-sum. When there's a winner for every loser, people start focusing on capturing their piece of the pie instead of collectively expanding it.

The Invisible Hand of Egalitarianism

Recall the invisible hand in economics: If there's money to be made, someone's going to make it. There’s a similar invisible hand in politics: If there's power to be grabbed, someone's going to grab it. In economics, you do this by giving your customers what they want. In politics, you do it by giving voters what they want.

While economic firms promise profit, political firms promise status. Interestingly enough, both of these can be wedges to get the other.

Why do we have firms in the first place? Per Ronald Coase, it's easier to organize in a corporation than as freelancers (e.g. "transaction costs").

Similarly, political parties are arguably the most effective vehicles we have for enacting political action.

The same way corporations seek certain types of employees and avoid others (i.e. being too "entrepreneurial" may mean those same people will be quick to leave), political parties are incentivized to look for their specific type of person (e.g. loyal, dependent people).

This is why Marxist rhetoric is highly effective — especially when people aren't getting rich. Elections are won by majorities. The political playbook goes something like this: politicians tell lower status people “vote for us, and we'll give you high status; Don't vote for us, and you'll remain low status.” When there aren’t clear paths to making a lot of money, people will search for other paths to status. And following a political tribe offers a pretty appealing option. This is why political power doesn’t like The American Dream: people making money is a threat to its power — just like how capitalism was a threat to communism.

Political parties don't even have to deliver on their promises. Since they're inherently against the establishment, they can continue blaming the establishment for the lack of change. For better or worse, being unreasonable gets you more loyal followers than being reasonable. This is because reasonable people are likely to have more options, whereas unreasonable people “burn the boats” and are thus more likely to remain loyal from killing all their other options.

Any good political agent will organize these people in order to increase their own status/reputation — similarly to how any good commercial agent will find a way of making more money.

Promising equity is an accelerated path to power for a politician: If you’re below average, “equity” means “boost in status,” meaning half of the population is incentivized to advocate for redistribution on a pure short-term status calculation. The only way to enact this at scale is to increase state power —which is why that option becomes so politically appealing. It’s an easy way to get voters and justify the expansion of state power.

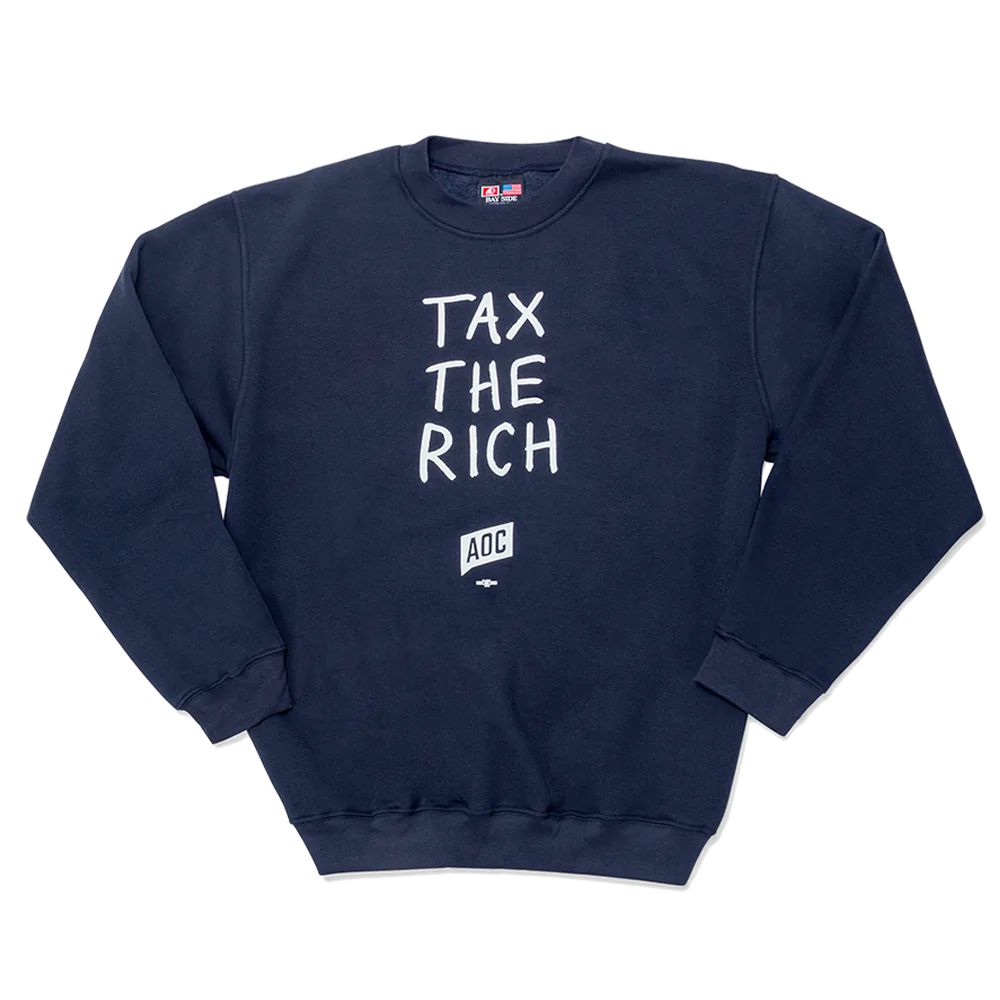

This same status dynamic explains why Marxism is ironically good business rhetoric. It’s the best example of capitalism’s greatest super power: its ability to absorb anti-capitalism and sell it back to consumers as a luxury good.

What this boils down to is that in any society that caters to individual preferences— whether as voters or consumers—ideas that promise people greater status (e.g. redistribution) will gain significant adoption. This is the invisible hand of egalitarianism.

Thanks to Molly Mielke

It's Ronald Coase (nor Coarse).

You might enjoy the book "Envy" by Helmut Schoeck (recommended as one of his favorites by Bryan Caplan).