On Ambition

A follow up to "Hustle Culture"

Last week we talked about how the term “hustle porn” is often used to stigmatize working hard altogether, and how there’s been a culture shift from celebrating Michael Jordan’s perseverance despite the flu to celebrating Simon Biles’ courage to drop out of the Olympics despite potential blowback.

I heard three interesting responses that I’d like to address in this piece.

Why is ambition good in and of itself? Why be ambitious in work, as opposed to ambitious hobbies or other things?

Why work hard if you’re an employee, not a founder?

Why not emphasize work-life balance for most people, given that they won’t become the next Elon, and the Elons will become the next Elon regardless of what the defaults are?

Let’s tackle these three in order.

Why be ambitious?

Whether it's R/Antiwork, one of the fastest rising subreddits over the past few months, 'billionaires shouldn't exist' emerging as a actual political position, or people going to Jeff Bezos’s house with a guillotine. there seems to be rising skepticism about ambition and the value of work in general.

Why is there such skepticism about ambition?

There are a couple distinct versions of this hustle culture critique: one is that celebrating a more balanced lifestyle, even if working less, is actually a more effective way of achieving more. There’s some logic to this. The idea that a more balanced lifestyle will make you a better leader is widely accepted business advice today, even if it wasn’t 20-30 years ago. The implication is that someone like Elon Musk or Steve Jobs succeeded in spite of not being balanced — that Apple or SpaceX would be better with a more balanced Steve or Elon.

Then there’s the other version of the argument that says maybe building companies like Apple and SpaceX isn’t so important anyways—that maybe it’d have been better for the world if Steve and Elon prioritized their mental health and happiness over slaving away to create new products.

There’s some merit to the first argument. Clearly, if someone is depressed or burned out they're unlikely to build the next Apple or SpaceX. And it seems like both people have genuinely treated other people poorly, which is unfortunate. One can aspire for their creations without aspiring to their example in other areas.

The second one — is SpaceX even that important? — is where I struggle, and I notice a similar thread in the “Billionaires shouldn’t exist” discourse (because there are no Apples without billionaires).

We spoke in the last piece about a rise in the prioritization of self-care over self-sacrificing in service of some greater end. Of course, sacrificing for something bigger than self only works if there's something bigger than self. Today there isn’t. When we got rid of God, we failed to fill that gap, so we worshiped ourselves instead.

The question becomes: could be bigger than the self? Maybe…building civilization? Helping us feed, educate, entertain, and protect billions of people?

There’s the techno-optimist version of this: inventing new energy breakthroughs, curing diseases, and becoming a multi-planetary species. Balaji articulates this vision here.

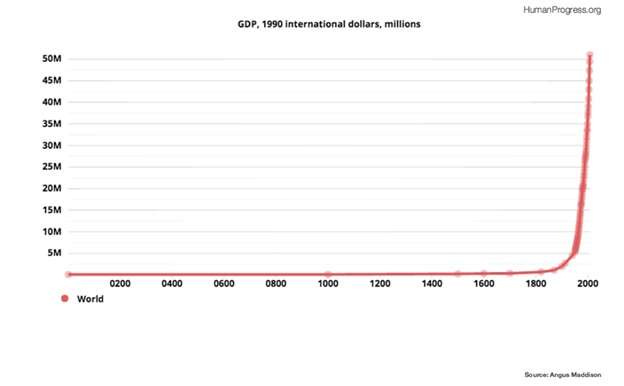

There’s also the more prosaic but just as impactful, “Getting people out of poverty”. Many people don’t work at companies that save the climate or cure diseases, but they do work at companies that contribute to economic growth. Increasing economic growth sounds like an abstract goal, but it does get people out of poverty. No matter your job or how meaningless you think it is, it’s likely you’re contributing to greasing the wheels of poverty reduction. Even if you work in finance! Even consulting!

I recently spoke to someone writing a book on how we need to find less meaning at work. I wonder if it’s the opposite: perhaps we should find more meaning in our work. Maybe the reason our jobs are meaningless is because we don’t connect the dots — we don’t see how our work makes an impact, we don’t see ourselves as part of the poverty reduction mechanism. It sounds too abstract, or too self-important, but that’s how it works. No individual was responsible for getting billions of people out of poverty, it was the efforts of billions of people working over long periods of time.

As a thought experiment, what if we changed “work/life balance” to “contribution/leisure (or self-care) balance”? Of course, there are many ways to contribute that don’t count as “work”. Some of them are even more important, like raising children. Being a great friend, partner, citizen are others.

But not all forms of leisure or self-care lead to increased contribution. As important as great TV can be, we didn’t feed billions of people watching Netflix. We did it by contributing to economic growth. We did it by working.

That’s my beef with the term “hustle porn” — putting down people who work hard and celebrate that fact is against our own interests, since expanding the pie propels society forward.

To be clear, we should also find meaning in things other than work and most people should prioritize them above work – having a family is likely the most meaningful thing you can do. (And, given population decline, likely also the most impactful!) But perhaps we’d also find our work more meaningful if we saw it as part of this interconnected human project that brings people out of poverty. Being a “cog in the machine” has a negative connotation, because we don’t emphasize how much “the machine” serves humanity. Just look at those numbers: We went from 95% of the world in abject poverty to 9% in under 200 years. Getting everyone out of poverty is the reason why we need to keep building. The positive version of “cog in the machine” is “being part of something bigger than oneself.”

The challenge is that people can barely see the impact their work has on their own direct stakeholders, let alone some abstract notion that they’re contributing to economic growth, which is somehow tied to eliminating poverty. There are too many abstractions for most people to intuit deep meaning from it. Which is a shame, because the process works despite people not grasping it. Unlike communism–now that’s an idea people grasp so much they’re willing to die for it. During the Spanish Civil War, soldiers were said to have died with the word "Stalin" on their lips. We don’t see people dying with “economic growth” on their lips

You wouldn’t die for this?

The fruits of your labor

One fair pushback to all of this is the response question I mentioned earlier: “it’s easy for founders to say we should work hard! But what about all the people who don’t have huge upside? Most people work in environments where the benefits of putting in disproportionate "hustle" accrue mostly to someone else, usually the owners of the company. Why should they find more meaning in their work, or work harder for less upside? In that context, hustle culture can be seen as a "conspiracy" (an emergent one, not an intentional plot) to get labor to work more for the capital's benefit.”

To that I say, firstly, everyone should decide what makes sense based on their own goals. Secondly, I’d agree! let’s give labor more upside (i.e. make them capital). Let’s find a way for everyone to get upside in what they work on, or even what they consume. Hell, let’s even consider doing some version of Universal Basic Income tied to the stock market so everyone becomes “capital” regardless of where they work. Yes there will always be inequality, but in an increasingly productive world, that does not preclude abundance for all. More practically, if people want founder upside, they should become founders. (And we’ll help!) But they also have to take founder risk, founder stress, and the all-consuming founder lifestyle. As revealed preference demonstrates, the founder risk/reward tradeoff often doesn’t make sense for most people. Which is great, since companies are built more by their employees than their founders anyway. And for big companies, employees get rich too. More broadly, we should better celebrate and reward the broader teams who build these epic companies.

What about the people who aren’t part of the next SpaceX?

The last line of thinking I want to address is the idea that we shouldn’t encourage people to become the next Elon, or to join the next SpaceX, because it makes everyone who won't, feel like a failure.

This logic is also related to the friend I mentioned earlier urging people to pursue meaning outside of work: The idea was that if you pursue meaning in work, you’ll likely be disappointed since you won’t be the next Elon or join the next SpaceX. Which is why we need to shift to a collective goal, so that more people can internalize the positive impact of their work.

There seems to be a tension between what we optimize for — the chance of creating more SpaceX, or the feelings of the people who can’t or don’t want to build the next SpaceX?

If we glorify SpaceX, then, inherently, there's some relative shame for the 99% who can’t join or build SpaceX. Some people debate the premise by saying things like: "Outliers will be outliers no matter what. Most people won't be outliers, and thus we should optimize such that those people are still happy."

In my opinion, a society looking to maximize its outliers needs shots on goal. To get one SpaceX, you need thousands of attempts. Thus, if we're encouraging less people to try to be the next Elon or build the next SpaceX, we'll get less Elons and less companies like SpaceX. (And this is the problem I have with the “maybe SpaceX isn’t important” argument.)

Some ask: "Why not just let people do what they want"? Well, people are influenced by culture. If we raise the status of becoming an Elon or building the next SpaceX, we'll get more, and vice versa.

There is always a default, so we have to pick: are we encouraging more companies like SpaceX or less? Are we raising the status of people who pursue SpaceX like companies?

Imagine the thought experiment where Elon Musk retires, spends time with his family and pursues internal fulfillment, and notes that relentless work made him miserable.

Many would celebrate this, noting that we have too many people burning out, depressed, even suicidal, all because they're working too hard and feeling ashamed for not being the best.

But what isn’t factored into this calculus is that if Elon stopped working — and if he inspires others to work less — society loses innovation and growth. We’ve had economic growth for so long that we just take it for granted. With billions of people still in poverty, we still don't have enough of it.

It’s also unclear if hard work is the main source of increased burnout. After all, there are two kinds of burnout: There's the physical form, usually caused by some combination of lack of sleep, lack of exercise, eating bad food, drinking too much—and certainly yes, working too hard.

Then there's the psychological form, which I think for many is not having a mission one is excited about and is able to make difficult but steady progress towards. The actual motivation for the work, and the ability to get in a flow state when doing the work.

This logic is also related to the friend I mentioned earlier urging people to pursue meaning outside of work: The idea was that if you pursue meaning in work, you’ll likely be disappointed since you won’t be the next Elon. Which is why we need to shift to a collective goal, so that more people can internalize the positive impact of their work, while also celebrating the individualism that inspires these businesses in the first place.

For the 99.9% who don't become the next Elon or join the next SpaceX, we should emphasize collective purpose/meaning bigger than our own happiness: a positive-sum mindset based on expanding the pie. The idea that they are enough and should be proud of what they are, but also aspire for more as a way to continue contributing. The dual advice of “You’re doing OK, and that’s OK, and yet, if you want to contribute more, you can and should also strive to be better and do more”.

“The problem is desire. We need to *want* these things. The problem is inertia. We need to want these things more than we want to prevent these things. The problem is regulatory capture. We need to want new companies to build these things, even if incumbents don’t like it, even if only to force the incumbents to build these things. And the problem is will. We need to build these things.” - Marc Andreessen in “It’s Time To Build”

Neither transhumanism nor economic growth/progress studies are accessible enough as a mainstream reason for why people are more ambitious. Progress Studies is inspiring to nerds (of which I am one) and Transhumanism is inspiring to Balaji and his fifty friends (of which I am also one). The Jordan Peterson narrative that working hard makes you more fulfilled since you’re proud of yourself is more accessible, but still only to a small subset.

Most people need to believe in some deeper purpose behind what they’re doing. We need a more accessible, transcendent narrative for why more people should be ambitious, especially if it comes as any form of sacrifice.

Thanks to Gonz, Michael, Sachin, Talal, Zach, Nadia, and Molly for feedback

“Then there's the psychological form, which I think for many is not having a mission one is excited about and is able to make difficult but steady progress towards. The actual motivation for the work, and the ability to get in a flow state when doing the work…we need to shift to a collective goal, so that more people can internalize the positive impact of their work”

Agreed! Burnout happens when goals are not sufficiently motivating. And I think often they are not sufficiently motivating because they are not precise enough at some level. Elon’s goals are the most precise in the world, from vision down to daily tasks. It’s really hard to do, and we all need to figure out how to do it better.

The idea of "meaning" is at the core of this discussion. Most people cannot tie what they do every day to a higher purpose, therefore feeling "meaningless" and impossible to generate the effort required to succeed. For the minority that can (doctors, military service members, and professional athletes are great examples), it becomes all-consuming, almost addictive.

Sebastian Junger, a war correspondent and author, talks about his concept by saying, "veterans miss war because of brotherhood, the belief that you love those around you more than yourself." Their mission was the welfare of their community, which is why it was so hard for them when they returned. This phenomenon isn't unique to the military: athletes and healthcare professionals feel this powerful bond to their work and community. You can check out his full Ted Talk on YouTube: search "Sebastian Junger: Why veterans miss War."

What I'm trying to get at is that it's a dangerous game to assign one's "meaning" to their profession or, on a more fundamental level, their ambition. I say this as someone who's gone down this path and is still working through it years later. I wouldn't trade how I felt or the people I met for anything, but you can end up becoming a slave to your ambition.