On Hustle Culture

How our perceptions of hustle culture and ambition have evolved

I’ve been thinking about the concept of “hustle porn” lately. There are a few interpretations of what it means.

One is people who are busy but not productive — the visual of people bragging about how much they work or how late they stay up, but without getting that much done. Think motivational speakers. Or the people who post twitter threads about how to build things but who themselves don’t actually build things.

Another is the idea that “hustle porn” is anything that celebrates working hard altogether. Say the idea that accomplishing anything epic requires sacrifice, and that you likely have to work more than 40 hours a week to do something exceptional.

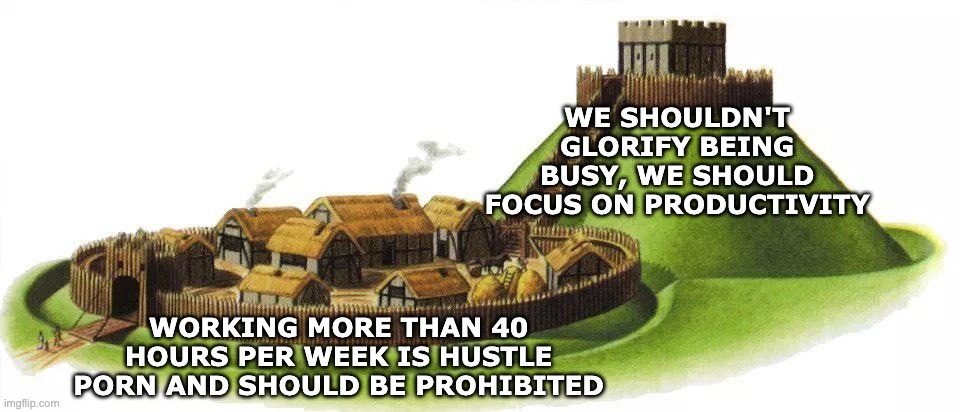

In other words, Hustle Porn is a classic Motte and Bailey.

A Motte and Bailey, as described by Scott Alexander, “is when you make a bold, controversial statement. Then when somebody challenges you, you retreat to an obvious, uncontroversial statement, and say that was what you meant all along, so you’re clearly right and they’re silly for challenging you. Then when the argument is over you go back to making the bold, controversial statement.”

So, in this case, someone says the idea of working more than 40 hours a week is hustle porn. When challenged, they retreat to safety by saying they mean “the bad kind” of hustle porn even if hard work itself is what they’re stigmatizing.

The term “Hustle porn” effectively becomes a weapon by which people can stigmatize hard work, merit, or even agency altogether.

(There are lots of Mottes and Baileys floating around our discourse. Exercise left to the reader to find them in the wild :))

Consider that we can apply the same Motte and Bailey to self-care by calling it “self-care porn”. We can describe self-care porn as someone focusing so much on their mental health they become depressed and neurotic about it and don’t actually take good care of themselves. We could then say, anytime someone makes a statement with regard to self-care, that they are engaging in self-care porn. But the “porn” connotation here is similarly obfuscating.

The increasing concern about “hustle porn” also seems to coincide with a rise in the prioritization of self-care over self-sacrificing in service of some greater end.

When I was growing up, many kids wanted to “be like Mike” — Michael Jordan was a ruthless competitor and put winning above all else. He bragged about how hard he worked, and taunted people who weren’t mentally tough enough for him. If he were coming up today, would he be as universally celebrated? Today he might have been accused of hustle porn, fostering a “hustle culture”.

MJ’s approach towards work was not unique to him by the way. Another popular example was Kobe Bryant (RIP), who cared so much about hard work he shamed a sixth grade basketball team for not working hard enough.

Contrast Jordan and Kobe to Simon Biles, the olympian gymnast who was celebrated for withdrawing from competition due to mental health. Wes Yang captured it well: “We would have urged people to empathize with Biles’ pain at any time prior to the summer of 2021; only today do we speak of the “radical courage” of withdrawal.”

Jordan was celebrated for playing with the flu. But today he may have been more celebrated if he had dropped out for mental health reasons. Indeed, the correct take on the Biles was “quitting was more wonderful and courageous than persevering.”

The difference is that Michael was expected to win despite his health. His health was seen as a means to an end, some greatness outside the self. Whereas now, since the arbiter of the highest good is the self (internal), not society (external), Simon had the courage to listen to herself over any external projections. “I’m doing me” is the noble path when the self is the ultimate arbiter of the highest good.

Courage used to mean sacrificing the self for an external aim. Now it means sacrificing the external aim for the self. “I have to be true to myself”

Jordan overcame his pain. Simon made the decision that was most authentic to her. It’s possible the latter is more respected today.

To be clear, Simon is also the GOAT at what she does, but she won Athlete of the Year for withdrawing, not winning, which only emphasizes the point.

Society’s choice of role models indicates what character traits they value above all else, and this tells us we prioritize self-care over sacrifice, of internal authority over external authority

It’s interesting to note that the increase in complaints around hustle porn also coincide with the shift in what society celebrates described above. Did the amount of hustle content increase, or did the perceptions of that same hustle content become more negative? I’d wager the latter.

For the avoidance of doubt, there’s a lot of genuine hustle porn out there that’s unproductive – for example, a person celebrating sleepless nights without actually accomplishing something valuable. But what the term “hustle porn” fails to do is differentiate between the productive content and the unproductive content. Which means that any notion of celebrating hard work can be deemed as “hustle porn”, whether it’s the good kind or the bad kind. Jordan bragged about how hard he worked, and that motivated him and others to be better. That’s the good kind of “hustle culture”. It’s not hustle porn. It’s winning. Or, in non competitive sports, being great. The term “self-care” does the same Motte and Bailey in reverse. Any behavior focused on the self can be celebrated as self-care, regardless of whether it’s productive or unproductive.

Alexandr Wang alludes to the nuance well in “Hire people who give a shit”. If you give a shit, you ultimately care about the outcome. So celebrating any process (“working hard”) that is divorced from good outcomes (“being productive”) is indeed ineffective. Giving a shit requires working hard and working smart. One without the other is insufficient.

We should retire the term, “hustle porn”, or “hustle culture” and instead delineate between productive & unproductive content/cultures. A productive culture celebrates working hard, but also exercising, spending time with family, and sleeping eight hours (I wake up without an alarm clock and recommend others do too). Kobe was also a girl dad after all.

Just like there’s unproductive kinds of hustle culture, there’s also unproductive kinds of self-care, even using self-care’s own goals as the standard of what’s productive.

In a previous piece we talked about the rise of therapy culture. To be clear, I think it’s great that we’ve destigmatized mental health. In 2016 I was an advocate for this movement within the tech community, and I still believe in it. The stigma was real, and destigmatizing it has helped a lot of people. But I wonder if we made it so high status to go to therapy that people feel like it’s no longer okay to be happy-go-lucky, or that that’s somehow lacking emotional depth to not have any issues.

Or put differently, I wonder if people think that being relentlessly ambitious is no longer aspirational, or that it’s in fact an indication of some deep seated weakness that needs to be fixed (“men will literally do X instead of go to therapy”), because it goes against the notion that you are perfect for merely existing, that any institution or external obligation asking you to change doesn’t recognize that fact—and that instead of pursuing ambitious external projects, you should pursue the ambitious internal project of being happy with yourself just the way you are. (These are not mutually exclusive, though there’s a natural tension.)

But maybe it’s OK to put your all for something bigger than yourself if you want to. Maybe it’s OK to have some chip on your shoulder. Maybe it’s OK to use your hang ups as fuel to pursue ambitious projects instead of trying to remove every last hang up. (In the same way it’s OK to do the opposite of these three things).

There’s this obsession with balance. Perhaps it’s ok to be slightly unbalanced, as long as it’s sustainable for you. As Navy Seal Shane Patton once said, “Anything worth doing is worth overdoing”. Or as George Bernard Shaw put it more nobly, ''I want to be thoroughly used up when I die, for the harder I work, the more I live.”

Maybe achieving extraordinary results requires some sacrifice. Jordan Peterson used to make this point about Fortune 500 CEOs: we all envy Fortune 500 CEOs for their fame and wealth, but maybe we don't envy them for how they get there, which is generally 30 years of 80 hour weeks and hundreds of thousands of miles of travel per year, being away from one's family half or more of the year, high levels of stress, and all the rest.

There’s often some deep seated motivation for why they work so hard. There was a great essay written a while ago (I can’t find it) which claimed that many of the great founders/CEOs are psychologically broken in some important way. And so they look towards company building to fix the brokenness, which, of course, it doesn’t, though it fulfills them in some other ways. But maybe it’s OK for these people to have chips on their shoulders that they use as fuel for their work. After all, society depends on them to keep the trains on time.

Of course, many CEOs aren’t broken, and being secure and successful aren’t mutually exclusive — but for the relentlessly ambitious, the people for whom no number or accomplishment is high enough and they’re never satisfied, why else would someone be like that without some chip on our shoulder? Something from childhood? An insecurity, a desperate need to prove oneself, prove enemies wrong, or outperform our parents or siblings…?

It’s interesting, for people struggling with mental health, we’ve destigmatized withdrawing in the name of mental health (which is great), but we’ve stigmatized people persevering in spite of their hangups. That massive chip on the shoulder needs to go, the logic goes. Encouraging that is not healthy. That’s hustle porn.

As mentioned earlier, this logic is part of the broader idea that you are perfect for who you are, and any institution or external obligation (e.g. The Olympics) trying to reorient yourself for some external goal is corrupting. The goal is more to feel good internally than it is to make some external contribution. Or more precisely, the best way you can contribute externally is to be yourself and to love yourself.

It’s in stark contrast to the idea that you’re born flawed, and institutions, far from corrupting you, actually make you better. That the goal is external contribution over feeling good. Or more precisely, the best way to feel good is by having contributed something.

The argument also assumes this idea that happiness comes from feeling good all the time, from feeling balanced. As opposed to another idea that happiness comes from having accomplished something great and being proud of yourself.

Maybe some people, in optimizing for short-term happiness, are sacrificing their own long-term happiness. We’ve always been somewhat confused about happiness anyway. For Americans, we point (culturally) to the Declaration of Independence and "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness". Naturally, we think we're supposed to be happy.

Well, except for three things:

First, it doesn't say we're supposed to be happy; it says we're supposed to pursue happiness. And it doesn't say we're supposed to pursue life or liberty! Just happiness.

Second, life and liberty precede happiness.

Third, it's not the "Declaration of Happiness," it’s the Declaration of Independence.

So the rank ordering is clear: Independence, life, liberty, then the *pursuit* of happiness. And good luck with that.

Although maybe pursuing happiness directly isn’t as effective. Perhaps happiness is more a by-product of the commitments you make: to a calling, a person, a community, to things outside of yourself. Maybe happiness is less something a wearable can tell you, and more your own internal perception of how your life is going. Perhaps to find out if someone’s happy you shouldn’t just ask them if they’re happy, you should instead ask them if they’re proud of themselves.

One of the amazing twists of the last 50 years is that "self esteem" is a concept from Ayn Rand's collaborator Nathaniel Branden. It started out meaning something like what Nietzsche would say and then transformed into the exact opposite: feeling good about yourself even when you have no reason to.

This is one of the things Jordan Peterson always pointed out in amazement from his world tour. He said, "I go to all these cities and I tell these people, you shouldn't have self esteem because you haven't yet done anything with your life to be proud of, and they don't get mad at me, they clap and cheer!"

"Why are they clapping and cheering? Because they've been lied to their whole lives, and they know it, and it's making them miserable, and finally someone tells them the truth."

"And now they have a way to think about what they should actually do!"

Thanks to Gonz, Michael, Sachin, Zach, Nadia, and Molly for feedback

I enjoyed this (especially the Kapwing watermark, thx)!

I think this shift towards “self-care porn” is partly related to the pandemic. So much public discourse and language was about taking a break from work, prioritizing public health over businesses, being generous to the unemployed, and staying in. Businesses advertised how their products could be used to better yourself at home, and those ads often glorified self-care. “Sacrifice for a greater good” became staying home and doing nothing vs starting businesses, building things, competing in sports, etc.

I would guess this will recede over the next few years as the public health situation has improved, because I do think some humans naturally want to achieve, compete, hustle, and build things.

one aspect of the discussion that i think is important to include is *who* the effort is in service of... i believe that one criticism of 'hustle culture' was the idea that it's mostly capital telling labor to work hard in service of capital. An empowered individual acting freely in the market on behalf of themselves, in a system that allows them to capture the output of their productivity is a wonderful thing. And healthy and sustainable. Hustling for oneself, vs hustling for others!