Reality is up for Grabs

Bootstrapping new realities in the digital age

Whatever your perspective is on the broader culture war, one thing is clear: we've lost our common sense of reality.

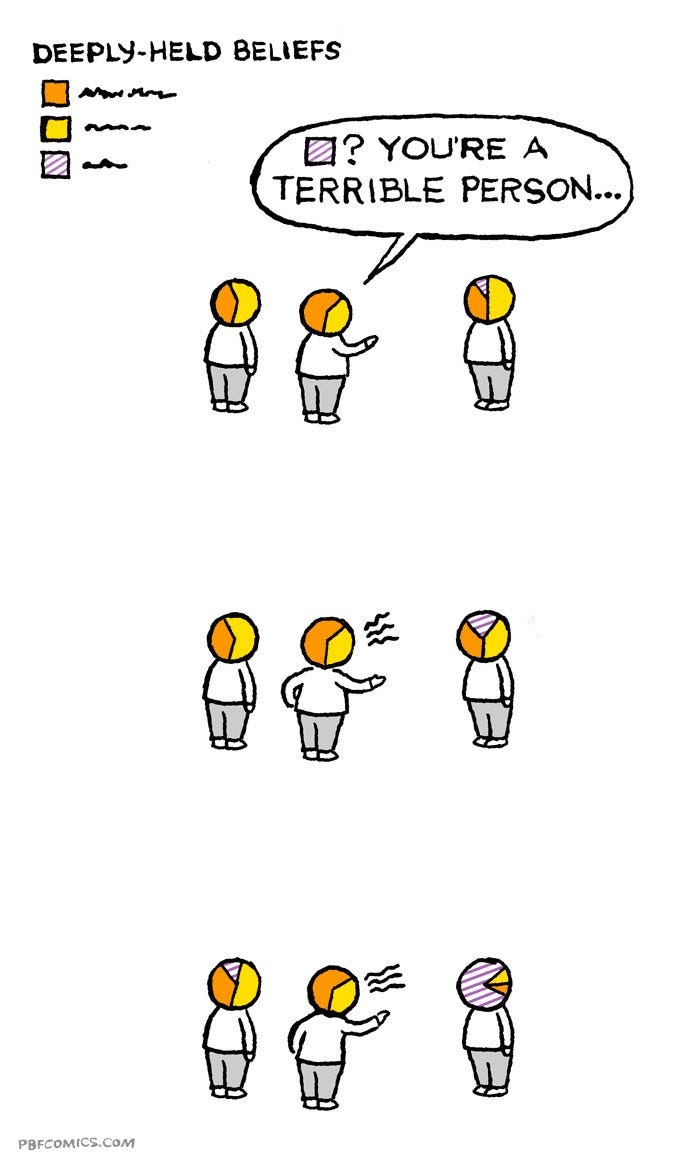

Trust in institutions is crumbling at the same time platforms for people to exit their own realities and enter new ones are growing. While the internet has democratized information sharing in a way we never thought possible, it did so at the expense of a shared alignment on, well, anything. Many feel pulled to one side of the political spectrum, often unable to strongman the other side's argument, leading to a divide in not just our body politic, but our broader world as well.

The problem isn't that we're arguing about morality or ideological differences, it's that we're arguing about the nature of reality itself. If two people can watch the same Youtube video, or read the same article, and come away with different explanations of what occurred in that piece of media, we clearly no longer have a central source of truth to understand reality itself.

Mike Solana aptly describes this connection to history as a tether — something that keeps us grounded in our shared sense of what's real and what's not. It's the way we can collectively track our thinking back to the source from which it originated.

I believe the tether has already snapped, and you can see this shift play out by looking at the prominence and decline of media technologies over time. As I mentioned last week, what began with broadcast media — a one to many dynamic that aligned us on shared information — has shifted to a more fragmented digital media landscape filled with creators pandering to ever-shrinking niche audiences. While we used to cohere around shared experience of watching the same TV channels, reading the same newspapers, and listening to the same radio stations, our niche outlets further fragment our now non-existent communities.

In other words, we’ve always disagreed, but at least we had the same coordinates by which we could disagree. Now we’re looking at different maps entirely.

Another shift that impacted on our sense of reality is the decline of print media.

Print media was a forcing function to move forward, enforcing a culture of progress. Since we recorded history in books, the general sentiment was about adding to the collective knowledge-base, not subtracting. Further, we remained tethered to the source from which that knowledge originated — we could look back and see how our thoughts started and evolved throughout history. And since it would be difficult to burn all the books we once wrote, we would keep writing new ones, further enforcing the culture of progress.

These days, however, we've been given the power to edit the past. As Solana says, "Information online is malleable, ephemeral, and nonlinear. Contributing to the human body of knowledge online is also dramatically easier to do than it was in an age of dominant print, and with a cost to contribute at something very close to zero. Because of this, contributions are made far more often, and far less carefully. With billions of people now connected to the internet, our digital spaces are flooded with noise. But what really sets the internet apart from print is the speed at which digital information changes."

The speed at which we can not only add to, but also subtract from, our collective knowledge marks a shift in how we understand reality. Instead of opening an encyclopedia and sharing a collective understanding of what something is, we can now change definitions and explanations of current events in real time to match the narrative we want to project. Problems arise when we try to reference old information, only to find that that thing has been changed, or even worse, deleted.

To be sure, to say that we ever had a real “shared reality” would be incorrect. We had a shared illusion, a simplified version of reality that Walter Cronkite truncated for us. Because there were only so few news-spreaders, you could hide so much information that complicated the story. In the internet age, that information can’t be held back anymore. The more information, data, perspectives there are, the more arguments there are over what even happened, let alone what it means.

I like to say that "reality is up for grabs," and though it's been harder to align on shared truths, we've seen many people take advantage of this shift in bootstrapping their own realities. It seems like the move to private membership communities is a sort of scramble to find one's reality territory in what feels to be a "new normal."

While some would just call this "community building," what we're seeing today is not just people aligning around shared values, but instead a shared understanding of the world around them. They're defecting from the mainstream narrative of reality, which used to bind us together, in exchange for new realities based on voluntary opt in.

It's interesting to see this happen in the most uncertain time in some people's lives — the COVID pandemic. In a way, we're all scrambling to find a leader with which we align, someone who can give us a sense of what reality is, or what it should be. For example, we could look at content creators as seed-stage "reality entrepreneurs," and their "fans" are consumers of — and investors in — the entrepreneur's model of reality.

What does this mean? On one hand, we're having incredible cultural innovation and a unique explosion of individualism. People feel they're able to share their authentic selves with the world, and as a result we're seeing new identities emerge with which people can align. On the other hand, this individuality comes at the cost of unity and a shared vision.

A friend of mine calls this kaleidoscope theory: culture fragments into thousands of shards, and each culture plays out its own fantasies alongside all the other cultures. The result is skyrocketing cultural innovation, at the cost of shared alignment on anything. A good tradeoff, assuming it doesn't lead to complete disaster.

America is an interesting test-case here because it faces a fundamental contradiction as a liberal wealthy society: we try to reduce conflict and protect people, and yet our media is fundamentally obsessed with violence and perversion. It's a contradiction between politics of safety and the aspiration towards extreme experiences.

We try solving this problem by allowing for the full range of human experience, but only at the level of virtual reality. VR is now not only a technology, as Bruno Macaes outlines in his great book, but also a metaphor.

In other words, the right provided America with the simulation of living through an incipient fascist dictatorship without actually delivering it. And CHAZ and Portland provided America with the simulation of living through a Maoist cultural revolution without actually delivering that. You can see it in the body count: real fascists & communists are too busy killing millions of people to take selfies for the ‘gram.

To be sure, while there have been riots and deaths (which I don't want to minimize the horror of), for the broader population, much of the culture war takes place on Twitter. Twitter makes you think we're living through the French Revolution, but meanwhile most of us are staring at our phones typing away about something we've yet to—and probably won't ever—experience.

And with no mechanism or infrastructure to adjudicate between competing realities, we're left in a position where these realities are not interoperable — they can’t cohere or reconcile with each other, unless perhaps faced with some existential enemy.

As a result, it seems that fragmentation will only continue, and “reality entrepreneurs”—community builders who make sense of the world and provide a vision of the future—will emerge to fill the void that this fragmentation creates.

Reality is up for grabs.

Thanks to Zach Davidson for meaningful contributions to the piece.

Read of the week: The Changing World Order, by Ray Dalio. Also this piece on the future of the MBA.

Listen of the week: Big Ideas season 2 is here! This is my alternative podcast where I interview historians, economists, and other thinkers that aren’t within the scope of Venture Stories. I release a season once a year or so.

I also spoke with Marc Andreessen about higher education on Venture Stories this week.

Watch of the week: Anthony Jeselnik joking about murder suicide. Note, if this humor doesn’t sound like it’s for you, don’t watch it! Anthony’s humor is not for most people.

Cosign of the week: Sar Haribhkati, who joined On Deck and will be leading our Fintech fellowship coming soon.