The Current Thing, Part 1

How and why it works

This first post in a three-part series describes how The Current Thing works. The second post outlines how The Bizarro Current Thing works. The third and final post discuses why both Current Things and Bizarro Current Things are impervious to rational conversations and nuanced debate. I also discussed this series on The Narrative Monopoly podcast.

In the last month, a new meme was born: “The Current Thing”.

The meme poked fun at the idea that every few weeks, there seems to be a new thing everyone is up in arms about, a new cause that you have to support or else you are a Bad Person. A new belief that everyone accepts in lockstep.

The idea of course spawned counter memes, implying that blind contrarians are just as unthinking as blind supporters.

Ironically, “The Current Thing” struck such a nerve that it was indeed The Current Thing for a few weeks.

What is The Current Thing?

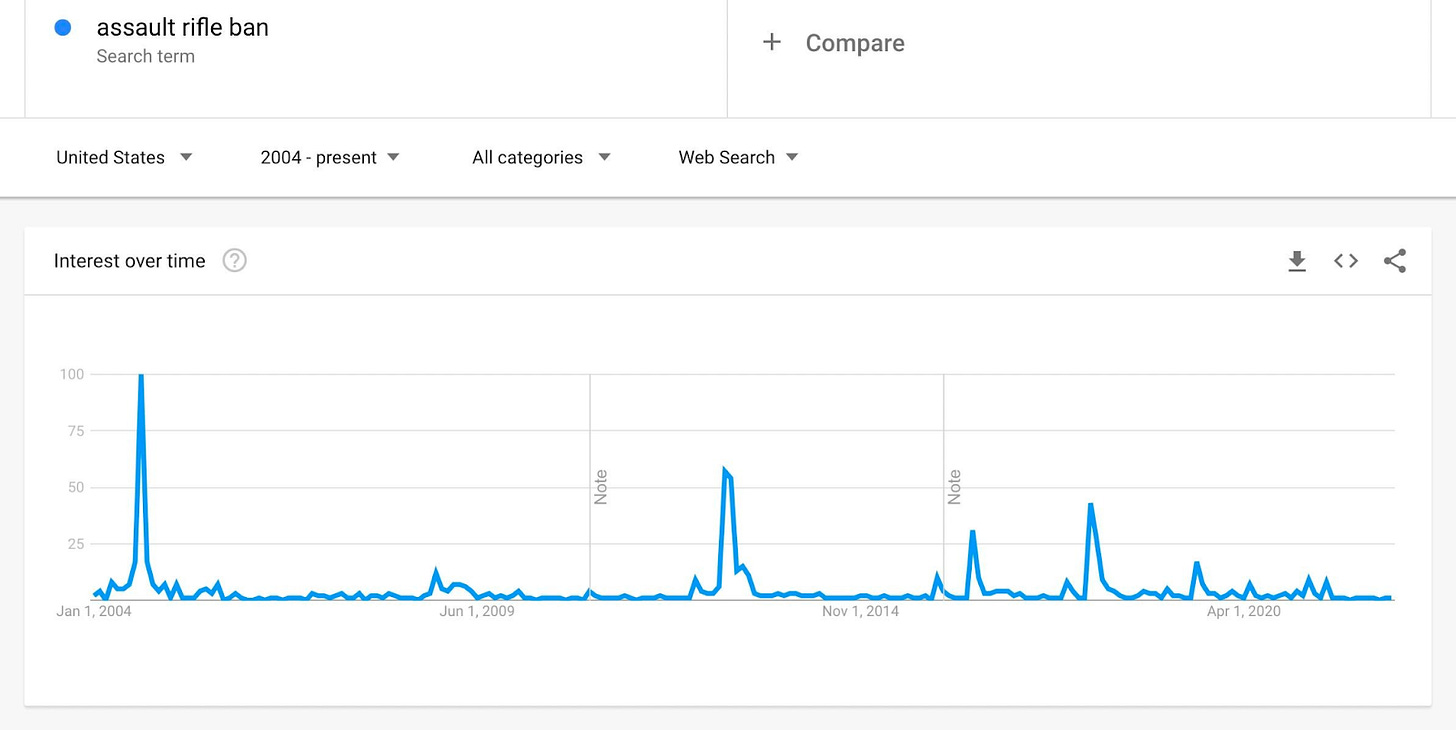

Per Marc Andreessen, the technical term for the Current Thing is "availability cascade", a combination of a social cascade and availability bias. The availability bias describes the idea that people tend to focus on the things that are right in front of them, the thing that is most visible. The social cascade describes the process of an idea gaining more and more steam, like an avalanche.

There are a few different flavors of Current Things. Sometimes The Current Thing is the rally against an abstract virus (e.g. COVID). Sometimes it’s rallying around a war with a clear enemy (e.g. Ukraine/Russia). Sometimes it’s organizing around a social cause (e.g. Same-sex marriage). Sometimes it’s around a cancellation of a person (e.g. Too many to name. See this list)

Mass cancellations can be partly explained by Girard’s ideas of mimetic desire and the scapegoat mechanism. Interestingly, Girard points out that this phenomenon develops even by people who are fully aware of the pattern. Each time, the death of the scapegoat is uniquely required by the specialness of the situation. And the absolute moral requirement that this time there must be mob justice. “This time, It’s not political—it’s moral.”

Are Current Things true?

There are various ways of interpreting Current Things.

A charitable view is that it’s the wisdom of crowds surfacing the most important problems as well as the best ways of solving those problems.

A less charitable view is that Current Things are “continuous overlapping sequence of emergencies, awakenings and panics, driven by the same interlocking power centers, demanding ever tighter censorship of speech and thought.”

An even less charitable view is that Current Things, paraphrasing Balaji, are the social equivalents of pump and dumps: They are pump and dumps for clicks for the journalists, votes for the politicians, and dollars for the activists. After all, the business model of the press & social media might as well be to cause the reader as much outrage as possible, every day, to cause fear and panic and drive them to come back tomorrow.

These are all interesting observations — that Current Things involve everyone converging onto the same beliefs and that there are profit motives for increasingly surfacing New Current Things — but they undersell the truthiness of The Current Thing.

Current Things always have elements of truth to them, otherwise they wouldn’t capture the world’s imagination. If they didn’t contain at least some kernels of truth, they wouldn't resonate.

That said, there is also often something “off” about The Current Thing as well. If it were so obviously, incontrovertibly accurate, it wouldn’t go viral, since everyone would be convinced already. There’s no need for evangelism when everyone is already converted. What goes viral is often what creates controversy between groups, where people retweet & quote tweet as a way to claim what side they’re on. If they don’t speak up, their tribal loyalty is questioned. Hence the phrase “silence is violence”.

Additionally, for a moral incident to go viral — for it to be The Current Thing — it has to be super clear-cut. And real-life events usually aren’t that clear-cut. And so the things that tend to go viral are caricatures, with the messy complexity stripped out.

Why do Communities Have Current Things?

While there are Current Things that become global Current Things, there are also localized Current Things. Turn on the TV and you’ll see Current Things 24/7, whether it’s CNN, FOX, ESPN—anything. All communities have their Current Things: their sacred cows which they invoke to enforce behavioral norms.

Jonathan Haidt, in his book “The Righteous Mind” explained the purpose of Current Things when he wrote “Morality binds and blinds.” Current Things bind people together over common beliefs, and they blind people to independent thought outside of the collective, since independent thought can at times be an impediment to group identity. More specifically regarding blindness, people become unwilling to critically analyze the Current Thing if it goes against the belief, precisely because that analysis is a threat to the coherence of the group. When this happens at the group level, this becomes The Madness of Crowds, as opposed to The Wisdom of Crowds, which we usually get when everyone is thinking as a rational individual, not when they are delegating their opinions to the zeitgeist.

So, Current Things may be true, it’s just that truth has little to do with whether what becomes The Current Thing. The Current Thing is not about people trying to find truth, it’s about people expressing loyalty to their group. I’ll elaborate more on this in Part 3.

What about the marketplace of ideas?

To me the most striking thing is how universities, media, and non profits have all converged. Why do Harvard and Yale and NYT and Wired and Vox and the Ford Foundation etc. all have exactly the same ideology at each point in time?

Harvard 2020 is very different ideologically from Harvard in 1990, but identical to Yale 2020. And same for the newspapers and magazines and foundations and research centers and philanthropists and comedians etc etc etc. Isn't rule number one in business, even in nonprofit fundraising, differentiation?

The top performers at the top universities, the top publications, the top non-profits—All those incredibly smart people looking to succeed in the world of ideas. Wouldn’t you expect a huge diversity of ideas?

If reality is becoming increasingly fragmented, as I posited in Reality is Up for Grabs, then how do we reconcile that with the observation that we’re all also converging on the same Current Things?

“A friend of mine calls this kaleidoscope theory: culture fragments into thousands of shards, and each culture plays out its own fantasies alongside all the other cultures. The result is skyrocketing cultural innovation, at the cost of shared alignment on anything. A good tradeoff, assuming it doesn't lead to complete disaster.”

How can we simultaneously have culture fragmenting into thousands of shards and also an intellectual monoculture? A few explanations:

We referenced the Girardian explanation above, mimetic desire: People don’t believe things because they instinctively believe them — they believe things because other people believe them. They feel if they could believe those things, or the status believing those things bring, they would attain some of the benefit they imagine the other person having from believing Current Things.

We also referenced Haidt’s explanation above: Morality binds and blinds. Group coherence is not formed when people think independently, but when people demonstrate unquestionable loyalty. Per Marc Andreessen again, the purpose of The Current thing is to classify friend and enemy. Nobody wants facts about The Current Thing. We want to know who’s friend and who’s enemy. The crazier the belief, the better it is for tribal bonding.

There’s also a simple explanation and a complex explanation for how the internet accelerates Current Things:

A simple explanation would be think of social media as turning the whole country/world into one huge oral tribe. And what do tribes do? Gossip, scapegoat, and converge on similar beliefs! Social media is just one big high school cafeteria.

A more complex explanation would be applying Ben Thompson’s Aggregation Theories to ideas, as he did here. To briefly explain Aggregation theory:

Pre-internet, you captured profits by controlling supply. Now, post-internet, you capture profits by aggregating demand. Further, the internet made the marginal cost of distribution go to zero, implying that adding one additional customer is as simple as adding one more row in a database. It’s virtually free. This means the best companies win by providing the best experience, which earns them the most consumers/users, which attracts the most suppliers, which enhances the user experience in a virtuous cycle.

Put differently: if you own all the users (e.g Google, Facebook), you're not going to charge them exorbitant rents like pre-internet monopolies used to do. You're going to charge everybody else who wants to get to those users and sell them goods and services or certain ads or whatever it might be.

This process of aggregators getting bigger and bigger, according to Ben, also applies to ideas: the best Current Things aggregate more and more believers with zero marginal cost.

What Ben also realized is that, while the aggregators get bigger and bigger, the long-tail gets bigger as well. He calls it the Internet Rainforest: in a rainforest, two types of plants thrive: the tiny, highly differentiated plants on the forest floor, and the giant trees that form the canopy. It’s hard to be in the middle. The internet introduces every industry to this barbell-like distribution.

I gave an example of this bifurcation in “The Death of the Middle”:

“The emergence of department stores opened up a vast array of choices for the everyday consumer. No longer did they have to go to the corner store and hope their store clerk was selling what they desired — these massive stores offered a larger selection of products at cheaper prices. Sears, Macy’s, JCPenney — these were all great businesses.

Until the internet and Amazon came along and reshaped the industry to fit a barbell distribution. We saw an explosion of higher quality products at lower prices (from better economies of scale) on one side and the rise of the boutique or the rise of specialists (Gucci, Apple, Lululemon, etc) on the other. So department stores got destroyed. Malls got destroyed. Anything that was in the middle got destroyed.”

This barbell bifurcation is happening across many other sectors, including media, music, and even VC ….While we all used to listen to the same ~100 bands, now global hits are bigger than ever, and the long tail is bigger too. The middle has been hollowed out.”

So it seems that two things are true: On the one hand, thanks to the great fragmentation enabled by social media and the explosion of information, we have thousands of bespoke realities and reality entrepreneurs seeking to define them.

On the other hand, thanks to mimetic desire, social psychology, and social media, the mainstream converges to an intellectual monoculture that becomes more and more shrill in its attempt to fight the reality entrepreneurs away.

This is how Current Things encourage ever-increasing levels of rigid lockstep, even as independent media fragments into a thousand diverse intellectual shards.

In our next pieces we’ll take a deeper look at why Current Things are impervious to rational conversations, how mass oppositions to Current Things have Current Thing-like dynamics, and why the crazier a Current Thing is, the more likely it is for people to believe it and spread it.

Thanks to Marc Andreessen and Balaji Srinivasan for their writing and conversations on this topic, and to Molly Mielke for brainstorming and editing

There is a dynamic that opposing the thing strengthens it. The one crazy in the store not wearing his mask reinforces the feeling of unity among the maskers for instance.