There's Just Too Many Damn Elites

And not enough high-status cushy jobs to go around

In a recent piece on James Burnham we discussed the rise of managerialism, or the idea that society is dominated neither by capitalists/owners or workers/proletariat.

Instead they are run by a middle layer of managers who have entirely different incentives from the owners or the shareholders.

In this piece we’ll do a deep dive on this managerial class, how their activism has evolved over time, and how activism serves their professional interests. We’ll draw upon the work of Catherine Liu, the author of Virtue Hoarders, and Malcolm Kyeyune, both of whom articulate a critique of the PMC from a left-wing, working-class perspective.

While Burnham introduced the concept of managerialism, Barbara Ehrenreich coined the term “Professional Managerial Class” in her similarly-titled 1977 essay. Since her piece, the PMC has only grown in power: eating up most of the money in our society while acting rebellious and aggrieved while doing it.

Marc Andreessen called the PMC the ‘laptop class’:

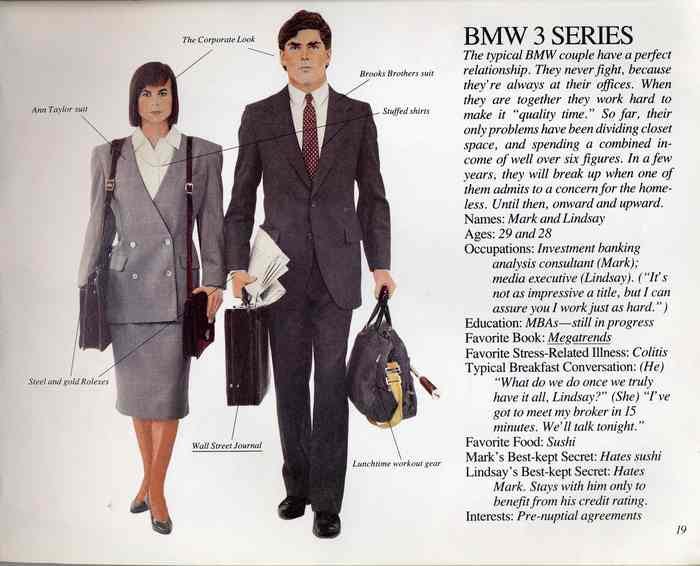

Laptop Class (noun): Western upper-middle-class professionals who work through a screen and are totally abstracted from tangible physical reality and the real-world consequences of their opinions and beliefs.

The professional–managerial class tends to have incomes above the average for their country, with major exceptions being academia and print journalism." [Who are compensated with power instead.]

The PMC exists somewhere between what we think of as the traditional working class and the ruling class. While they aren’t capitalists and don't own the means of production, they do play a big role in upholding and extending capitalism’s reign.

In other words, managers are a specific type of employee that are materially on the side of labor—but symbolically on the side of capital.

What Ehrenreich noted was a bifurcation: On the higher end more commercial PMCs were peeling off to join the elite tier of wealthy CEOs and managers, while on the lower end the PMCs were suffering from a collapse of many of their preexisting professions (e.g. academics, journalists, etc).

And so the academics and journalists had to make a choice: they could either join the traditional working class to fight against the capitalists or they could join the capitalists against the working class in the hope of getting rich in the process.

Post 2008, we saw the PMC join the working class to fight the capitalists in the Occupy Wall Street Movement. The majority of Occupy’s participants were college grads who had experienced massive student debt, unemployment, and downward mobility during the economic downturn. The language of “We are the 99%” reflected the fact that the movement’s participants saw themselves as part of the exploited masses.

But the Occupy movement quickly came and went. Corporations obviously didn’t support it because unlike more recent social movements, Occupy required real sacrifice on the part of the corporation. Bernie Sanders ended up losing to Hillary and that was that.

In an attempt to create these new social conflicts (anti-racism, anti-fascism, the gender wars), the PMC altogether ignored and suppressed class wars. When Nike says they’re committed to fighting anti-racism or anti-semitism, it buys them social capital that allows them to deflect against inquiries into how they treat their workers.

Over the next decade that PMC would eventually switch from working class to social justice rhetoric. After all, Wall Street couldn’t support Occupy Wall Street or broader unionization efforts while remaining in business, but they could fund activist efforts with billions of dollars while signaling to the type of elites they’d like to hire and do business with.

To further distinguish the PMC from the working class, colleges initiated the PMC into this esoteric language which made non-college goers feel left out and left behind. A great deal of what constitutes activism is an elaborate set of rules about what you can and can’t say about this or that group. The complexity of the rules is itself strategic — it’s a way of doling out power to the college grads who learned all the rules while taking away power from the non-elites who didn’t.

Activism became not just a social philosophy, but an elite status marker. As David Brooks once put it, “You have to possess copious amounts of cultural capital to feel comfortable using words like intersectionality, heteronormativity, cisgender, problematize, triggering, and Latinx”. More specifically, you have to go to college to learn those words, which excludes two-thirds of the country.

Activism also became a strategy for professional advancement beyond college. By calling out the privilege and moral failings of those above them in the corporate pecking order, young elites became able to intimidate Boomer administrators and usurp power from them.

This isn’t all just ideological posturing, it’s also a practical necessity. The truth is that we have too many college educated people without technical skills who expect high-status and high-paying jobs and there simply aren’t enough jobs for them. So the posturing isn’t only a way to signal high-status, it’s also a way to ensure they continue to hold an elite job.

There’s just too many damn elites

Summarizing Elite Overproduction theory: The problem with having too many elites is that we don’t have enough cushy jobs for them. As the number of elites expands, there's a growing pressure to find roles for them so that they can keep their luxurious lifestyles. Thus, the state steps in to create roles for these excess elites that are appropriate for their status. The state can’t create jobs for all of them, so the private sector is expected to step in as well, hence the explosion of administrative jobs in companies.

As the elites continue to expand and the state struggles to find roles for them all, we begin to see intense competition for the few positions that exist. In the face of losing out on the money and status they expected to get, elites become very angry and turn on each other, creating intra-elite conflict.

One signal of intra-elite conflict is an emphasis on credentialing. In the old days when the majority of the elite youth could expect to inherit their parents’ wealth and status, they didn't bother to go to university. But in the wake of elite over-expansion, we watch them now fight for credentials as a way of distinguishing themselves.

This can be seen in the data: in the UK since 1990, population has increased by 15% while the number of students has increased by almost 100%. Similarly, in 1990, American Law school grads had an even distribution of salaries, but by 2000 a separation grew between winners and losers. We're feeding students a lie that a university education is their "golden ticket" into a class they probably won't make it into regardless of whether or not they receive a diploma.

Elite overproduction isn’t a result of a higher population as much as it’s a result of high expectations from the existing population. Specifically the idea that anyone, if they work hard enough, can earn — scratch that, deserves — a path to the elite class. Globalization amplifies this significantly, while the internet takes this phenomena to even further extremes. This means that the whole world now expects to become part of the elite class.

We think of revolutions happening because the masses are poor and angry. While that’s probably part of it, revolutions are more often the product of intra-elite competition that leads to a counter-elite class who, feeling entitled to money they won’t get, fight to ensure others won’t get what they so desire either. The common misconception is that revolutions start from the bottom. But that idea doesn’t hold up if you look at history — the people behind the French Revolution weren’t poor. Furthermore, since the elite control the army, they can usually keep the masses from organizing.

Activism as a PMC response

Malcolm Kyeyune has an interesting thesis around all this: He noticed that many jobs in the professional class — academics, journalists, activists, bankers, consultants, middle-managers — lack clear accountability. They claim to hold others accountable but have little accountability themselves, neither to the market nor the electorate. The most ambitious people sometimes self-select out by becoming entrepreneurs. Conversely, bureaucracies attract people (on average) who conform, which means that these bureaucracies become increasingly run by people who prioritize conformism over quality. You see this in Corporate America too, where the organization is increasingly influenced by HR and PR.

But why is this? Malcolm argues that conformism is a survival strategy in fields that don’t have radical accountability. If you're of the working class, your work speaks for itself: you either mine the coal or you don’t. Similarly if you go to the opposite end of the job complexity spectrum and look at rocket scientists, either the rocket works or it doesn't. At both the top and the bottom, you either do the thing or you don’t. But in the middle, as a worker you are often incentivized to play politics since people’s opinion of you is what determines your performance. In areas where you can’t show your work, perception becomes reality.

This is why we see something akin to Orwellian groupthink among corporate executives, investment bankers, elected politicians, civil servants, and nonprofit leaders. They all hold the same views and reinforce each other as they move laterally in their careers. Diplomats become investment bankers, investment bankers become ambassadors, generals sit on corporate boards, and corporate executives sit on nonprofit boards.

What this means is that we've created a huge surplus class of administrators in our imperial machine. And there's simply not enough things for them to do since all the manufacturing is done somewhere else. So one way to view some of these activist-oriented jobs is to see them as a make-work program for elites. There is a whole web of managerial technocrats, government regulators, activists, people who run media orgs, NGOs, etc that helps serve this goal. To be sure, there’s lots of great people doing important work at philanthropic organizations, but there are also plenty of people at both private and public sector organizations who are claiming to be doing important work but are not actually having an impact—and there’s often insufficient accountability mechanisms to do something about it. As we just saw with the FTX blow up, just because someone claims to be doing good does not mean they are.

When activists advocate for new rights, they’re also implicitly advocating for a permanent cast of managers to monitor the implementation of these new rights. This is why some of the problems the multi-billion dollar activist class was created to solve will in fact never be “solved”. It’s a challenge of incentives: people are less likely to solve a problem if solving the problem means losing their jobs.

The PMC of course wants to retain high-paying jobs as consultants and communicators — And for many years, companies could get away with a bit of excess in the name of social impact (and good marketing). But with increased interest rates and a deteriorating macroeconomic environment, these roles are increasingly harder to justify.

This is partly why there’s so much concern over Elon’s mass layoff at Twitter. From Malcolm’s post on the subject, very bluntly put:

In America, that jobs program is only partially covered by the state. Private companies like Twitter have therefore been expected to shoulder the burden and make sure the scions of the professional-managerial class can find lucrative work, even when there is no real economic reason to pay them. That system is now buckling under the sheer amount of waste that can no longer be covered up by cheap money and easy debt. Musk makes a useful scapegoat here, but none of this is his fault, nor could he change this dynamic if he wanted to.

The people who worked “on climate” at Twitter, now being given the ax by the perfidious Elon Musk, are openly complaining that they won’t be able to find jobs anywhere else in this economy. They are, of course, right to worry. One of the biggest and least-talked-about social questions in the West is how to economically provide for our own modern version of France’s impecunious nobles: that is, how to prop up high-status people who can’t really do much economically productive work.”

We need people working on climate, and on all sorts of important social issues, but we need people doing them in smart and accountable ways, whether private or public sector. Markets and elections should enforce this accountability, but for whatever reason they aren’t.

This is where we come full circle to where we began this piece. This is a unique phenomenon in that even Marx and Adam Smith probably couldn’t have anticipated it: it's neither the customer nor the owner of the capital calling the shots. Surprisingly, it’s not even the state calling the shots. Instead it’s a new managerial force colluding across the private and public sector, accountable to neither the electorate nor the market, all trying to maintain their high-status and high-paying jobs in an increasingly brutal labor market.

So you get what you’d expect in such a system.

Thanks to Molly Mielke

Surprised to do a CTL-F for "Turchin" and draw a blank

Really enjoying this whole series on the elites!