On this week’s Moment of Zen, we discuss many of the themes from this newsletter: egalitarianism eats the world, Christianity’s moral innovation, and the theme for this week’s post—how Slave Morality won.

On Cognitive Revolution, we did a deep dive on Stable Attribution with Anton Troynikov

Note: This is part 1 of 3 of my attempt to summarize Brett Andersen’s ideas. In this three part series I quote him at length. If you notice a good idea, consider it his. Related to this piece, read this for the full dose.

We’ve talked about how Christianity led to an inversion of values — from the veneration of the strong to the veneration of the weak.

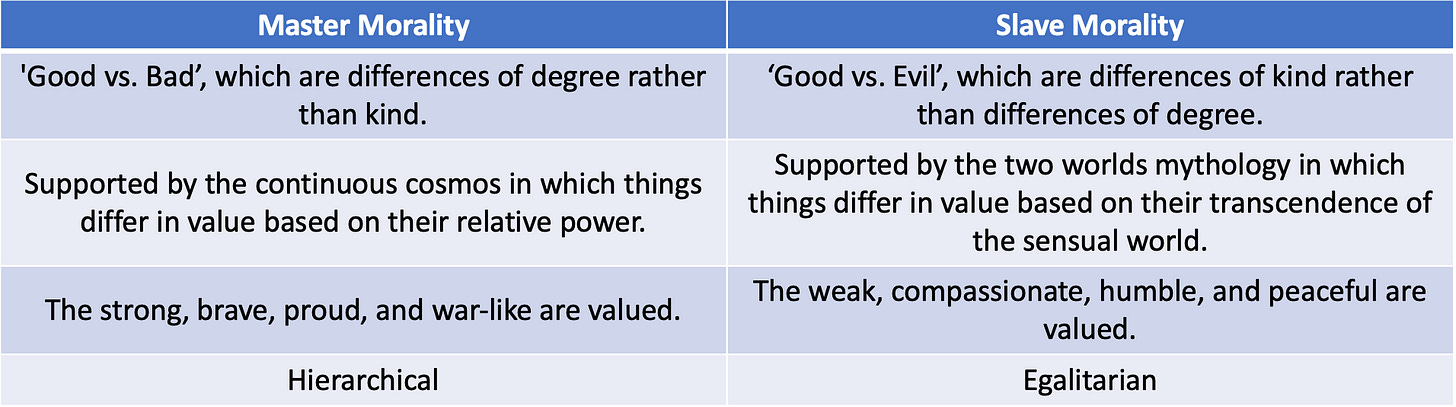

Zooming out: Prior to Christianity, value system and myths were all oriented around strength, excellence, and achievement — or Master Morality. Christianity flipped morality upside down and introduced Slave Morality: “The first shall be last, last shall be first.“

In other words, Christianity reordered values in western society from veneration of the strong (Master Morality) to veneration of the weak (Slave Morality) — from condemnation of the weak (Master Morality) to commendation of the strong (Slave Morality). “The Meek shall inherit the earth”.

Out were the strong, the rich, the powerful. In were the vulnerable, the poor, the oppressed. Here was the value reorientation (taken from Brett Anderson’s great Substack post):

We’ve talked about how that inversion of values manifested in Justice Eats the World. Egalitarianism seeped its way into everything. Everything that can become justice oriented… becomes justice oriented.

We described the mechanism for how justice continues to eat the world: If you put in place a value system that prioritizes the vulnerable over the strong — as Christianity did — then justice will be defined by greater and greater valorization of vulnerability. As a result we see both more and more people claiming to be vulnerable and more and more people claiming to be working on behalf of the vulnerable. So every year that goes by, morality and justice gets identified as caring more and more about the weak and vulnerable. This is how justice eats the world.

But we haven’t talked about how Justice came to originally eat the world: How did this great inversion of values occur? Where do Master Morality and Slave Morality come from? How have they manifested over time?

Where morals come from

As we’ve discussed, humans optimize for reputation, social status, mate acquisition, and a host of other things because valuing them served the inclusive fitness interests of our ancestors.

As a result, what we perceive as morally just is likely whatever optimizes for one of those aims. We deny this, of course, often because we are oblivious to it ourselves. Morality often conceals self-interested motivations, even to ourselves.

Nietszche held that people’s moral claims are often reflections of their own unconscious drives. Someone might promote Master Morality when they’re the strong one, and Slave Morality when they’re the weaker one.

In other words, people tend to adopt Master Morality when it suits them and Slave Morality when it suits them. Societies do the same thing.

The book, The Sovereign Individual, talks about the logic of technology determining the logic of violence: “When individual protection is hard, we rely on others to protect us—governments for example protect us externally with the military and internally with the police. When technology makes protection easier, we rely less on the government to serve that existential role, which leaves governments with less power as a result. “

This same thinking applies to Master Morality and Slave Morality too.

Indeed. Master morality is appealing to leaders — that’s why powerful people tend to be more right wing or Master Morality oriented — because of course people at the top of the hierarchy are going to believe in hierarchy.

Conversely, slave morality appeals to everyone else. Slave morality says hierarchy is bad and we should be more egalitarian. In fact the lower on the totem pole you are, the more pure you are. That’s of course going to appeal to people who are lower in the hierarchy.

So, what changed? Why did slave morality win? Two reasons: the evolution of warfare and governance.

As civilizations scaled, warfare became largely a numbers game, which meant that leaders needed to inspire their armies to fight for them. After all, armies with inspired soldiers do better than armies of slaves. Leaders who led with compassion and egalitarianism were more effective.

Of course, a military needs to have the best people fighting, so it ends up talking slave morality, acting master morality. Talk left, act right. You notice this tension still exists today. You need to speak a big game about egalitarianism to have popular support, but you need to be ruthlessly meritocratic in your organization to make sure you have great results. Without egalitarianism, a military won’t have popular support. Without meritocracy, a military won’t function.

In addition to warfare, the shift to democratic governance also led to slave morality. As we discussed:

“Promising equity is an accelerated path to power for a politician: If you’re below average, “equity” means “boost in status,” meaning half of the population is incentivized to advocate for redistribution on a pure short-term status calculation. The only way to enact this at scale is to increase state power—which is why that option becomes so politically appealing. [Slave Morality] is an easy way to get voters and justify the expansion of state power.”

So, for reasons of warfare and democratic governance, rulers started to adopt slave morality in their rhetoric as a way to win.

It worked. Christianity eventually became the official religion of the Roman empire and went on to become the most popular religion in the world. As we discussed before, when Christianity lost, it lost to a version of slave morality that was more Christian than what preceded it.

“At its core, all humanists, Marxists, and progressives want to find a way to justify Christian morality without Christian metaphysical belief. This comes off odd for people who believe we overthrew Christianity because of its primitive nature, but perhaps we overthrew it because we saw it as not Christian enough—not applying moral equality wide enough (e.g LGTBQ rights, among others). It’s fascinating to consider that perhaps when we denounced Christianity, we denounced it from a place of wanting Christian principles to be applied to a broader set of people, as opposed to saying Christian principles were all terrible in the first place.”

Indeed. What has often defeated slave morality is…more slave morality. Egalitarianism eats the world, the cycle continues.

> Conversely, slave morality appeals to everyone else. Slave morality says hierarchy is bad and we should be more egalitarian. In fact the lower on the totem pole you are, the more pure you are. That’s of course going to appeal to people who are lower in the hierarchy.

There is a study about how high T men in japan like hierarchy. So an example that runs counter to your narrative is that in Japan people at all places in the totem pole still respect master morality

While egalitarianism may be playing an ever larger role in our modern moral discussions, it doesn’t appear to be winning any significant tangible victories over the last few decades. Further, there’s a strong counter current in technology driving inequality by giving individuals and small teams ever increasing leverage and efficiency in deploying plans and capital. If anything, the recent flare ups of egalitarianism in our public discourse, eg. Occupy Wall Street and Bernie 2016, might just be a cathartic release of frustration for individuals who perceive themselves as getting the short end of the stick.

Similarly, while it’s been a while since I’ve read Nietzsche, I seem to recall him characterizing slave morality as being primarily a coping strategy for the weak rather than a calculated strategy for strengthening their position. While it could have the long term impact of subverting power structures, that was largely incidental. Its primary purpose was instead to allow the weak to accept their lot in life, and at times even celebrate their suffering. In contrast, active rebellions and revolutions required more of an Übermenschian will to power.

Hence, our recent preoccupation with egalitarianism may simply be the latest coping strategy for dealing with more saliently perceived inequalities.