The Sovereign Individual Investment Thesis

How the Information Revolution transforms us from citizens to customers of governments

Last week I wrote “The World According to Peter Thiel”. This week I want to dive into The Sovereign Individual, one of the books that most influenced Peter’s worldview, and explore how that relates to venture capital. Balaji Srinivasan turned me onto the book originally. His line on the book is that, if most books can be described in a single sentence, The Sovereign Individual is a book where many individual sentences can be expanded into their own book.

Written over twenty years ago, it’s amazing how much the book predicted correctly: The iPhone. Crypto. Rising inequality and corresponding unrest. The transformation from economic to cultural marxism. Rampant hyper capitalism. Even the rise of political correctness.

To be sure, the authors wrote other books, which had less correct predictions. But still. The Sovereign Individual was on the money. Both in what it has predicted to date, and also in the framework it gives us to help predict the future

First I’ll summarize the book and then I’ll describe the investment thesis that corresponds with it.

The basic thesis of the book is that technology, particularly the internet, will lead to unbundling & modularizing of government.

Put simply: We'll transition from being a "citizen" of government to a "customer" of government, where governments compete to earn our business.

The “citizen” construct implies that you exist to serve the government. Recall JFK’s famous speech: “Ask not what your country can do for you, but what can you do for your country.”

The customer construct, on the other hand, implies that governments exist to serve you. That governments, like any businesses, compete over earning your trust. And, just like in the private sector, this competition leads to better products, better service, and more innovation. The market serves as a filter—corrupt governments die out, and better and more competent ones remain. If Amazon and Apple provide excellent products and services, there’s no reason governments can’t either. Imagine housing, education, and healthcare, at the quality level of Apple and Amazon, for everyone.

What will cause the change from citizens to customers? Protection: When individual protection is hard, we rely on others to protect us—governments for example protect us externally with the military and internally with the police.

When technology makes protection easier, we rely less on the government to serve that existential role, which leaves governments with less power as a result.

The book claims that this phenomenon is the story of our time—that technology gives individuals and small groups the protection of a nation state—and as a result we will rely less on governments to protect us, since we’ll be more able to protect ourselves.

Long ago, this phenomenon—technology enabled protection leading to less reliance on external security—also occurred with chivalry. Chivalry wasn’t a romantic notion as much as it was practical—it was a protective mechanism against violence, before we had governments. As soon as better protective mechanisms emerged (e.g. government police and security), chivalry wasn’t needed as much anymore, and it became an anachronism. The book predicts citizenship will go the way of chivalry, and instead of being citizens of governments, we’ll be customers of them.

Here’s one implication of that: Customers can more easily leave and choose the option that works best for them. In future we’ll choose our jurisdictions and governments the way we chose our insurance policies or religions. Back then, choosing your religion was crazy, the way choosing our governments today seems crazy—or at least infeasible for most people. Soon, the book predicts, it’ll become normal.

The authors detail how this transformation—from citizen to customer—has mirrored other previous transformations in history, particularly how the agricultural and industrial eras led to the rise and fall of the church. Here is a radically simplified summary of the author’s retelling

The agricultural revolution led to some big changes over the hunter-gatherer era. We now had private property, long-term planning, and the specialization of violence, because now there was something to steal, namely food.

In the chaos of the agricultural revolution, The Church developed the moral authority to provide ethical frameworks. When the printing press emerged, however, it undermined the church monopoly on truth as it simultaneously created a new market for heresy. The church responded by banning books, similar to how governments today try to suppress encryption technology.

In hindsight, this makes sense. The more that people read, the less the church could maintain its monopoly on moral truth. Similar with governments, the more people build decentralized and sovereignty-enabling technology, the less that governments have a monopoly on violence. Which is why nation-states have a natural interest to fight wars—wars make nations and governments indispensable.

The Church was perfect for feudalism (legally, morally, culturally), but ill-fitted for the Industrial Age, because nation-states which were more effective for wars. Similarly, the state was perfect for the industrial era (economies of scale, centralization of violence) but ill-fitted for the Information Age, where decentralization is more important to better align knowledge and power.

What’s better for the Information Age? The Sovereign individual.

People didn’t mind giving money to church when there was no other use for it, but after they could invest and earn money, giving money to the church made less sense. Same with taxes and governments. As soon as you rely less on the government to protect you, and (more importantly) notice other options for governance, you start to more critically evaluate where your tax dollars are going. As competition emerges, you start to shop around.

Democracy in particular was most effective in building up the power of the state. This may sound intuitive, but democratic capitalism was an even more effective statecraft than communism, because it allowed people to at least earn money before it took a large percentage of it.

People see democracy & communism as different systems, but zooming out, they both rely on government allocation of resources. Similar to how people see Keynes & Friedman as different but, when compared to Austrian economics, they’re both governments manipulating the money supply in diff ways.

Democracy and governments more broadly were perfect for the industrial production era.

But, some people ask, won’t governments control the internet?

Governments have never established staple monopolies of violence over sea…. Meaning they won’t get cyberspace either, an infinite realm without physical boundaries

One other thing the book claims is that, until recently, technology has always led to increasing centralization. And for the first time, this trend is going to be reversed. That's what enables the Sovereign Individual.

OK. So that’s the book. What’s the investment thesis associated with it? In other words, how do we get rich? Well well well...

Zooming out….The internet is the great equalizer. On the internet, anyone globally can get a great education and build a portfolio.

The fact that anyone can build a portfolio means we’ll rely less on artificial gate-keepers of quality (e.g academia & media)

The fact that anyone can get a great education means people in developing countries can gain the same skills as people in developed countries.

This means companies will be able to hire people in developing countries at a lower cost.

This will raise growth and tax revenue in developing countries, but decrease it in developed countries.

To make up for lost revenue, developed countries will print money, raise taxes, and make it hard to leave (e.g. MMT, QE, Wealth Tax, Exit Tax)

Printing money means there'll be an increased demand for non-inflatable money, like bitcoin.

Increased tax means there will be an increased demand for charter cities. As mentioned, people will become customers of governments instead of merely citizens.

Let’s look at how several sectors may be affected:

Read of the week: The Once and Future Liberal: After Identity Politics by Mark Lilla.

Listen of the week: Justin Murphy on Internet Vitalism

Watch of the week: My friends at Krazam with an outtakes video.

Cosign of the week: Nasjaq is trying to fix the problem Peter Thiel spoke about, that nearly all sci-fi is dystopian, by making videos highlighting awe-inspiring technology.

Until next week,

Erik

Interestingly this plays out somewhat in South Africa. Mass unemployment, riots, failure of infrastructure and people leave to go to better places.

Exit and wealth taxes in place to prevent this.

So now the one prediction abput Governments wanting customers doesn't seem to play out. They all seem to want to destroy themselves by doubling down on bad policies. And they keep borders shut with large anti immigration visas and a pushback against globalization.

When do we get customer governments?

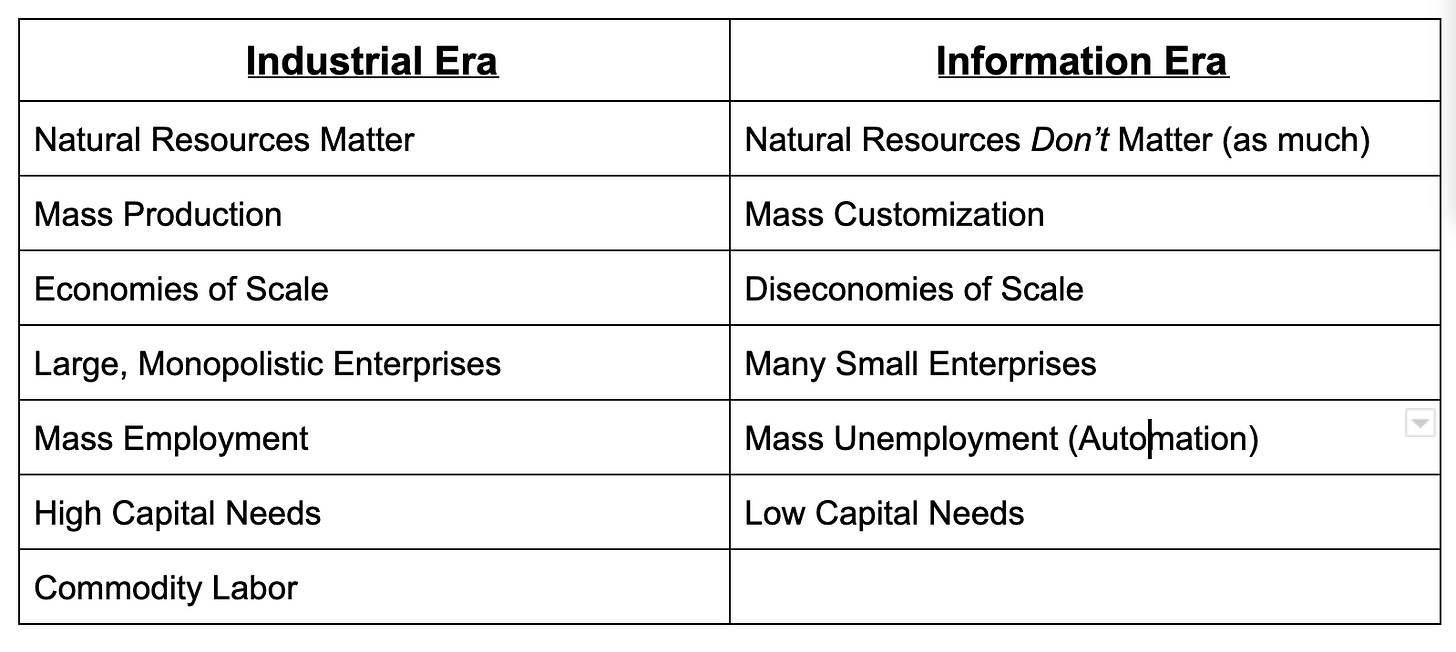

Lots of open-minded theorizing about an ideal information era, and it could have happened. But (as theory can be) reality finds us 180° off on every one of the seven predictions: Natural resources matter a lot (from oil, to neon, to territory). Rather than zero to one and customization, we see unprecedented billions of identical iPhones on Ikea tables…. Wright's law of experience still holds, but now multiplied by network effects resulting in massive economies of scale concentrated in a handful of enterprises. Unemployment has not materialized, but decades of waste sees human capital in short supply, while labour is commoditized.

Viewed this way, the second table of opportunities is instead a list of possible directions to regenerate society and steer back towards the ideal information era that was possible.