Housekeeping: For Upstream, I spoke with Agnes Callard about philosophy. For Moment of Zen, we spoke with Eugene Wei about the state of social media. For Econ 102, Noah Smith and I spoke about the fragmentation of libertarianism. For Media Empires, I jammed with Greg Isenberg about his personal holding company. And we just launched a new show, The Limited Partner podcast, with host David Weisburd.

In recent posts we’ve discussed why more people is better and why we need more immigration. In this piece we’ll defend trade trade.

Introduction to trade

There’s been great skepticism towards trade in the last few years, both on the left and the right. People blamed trade for job-loss, off-shoring, and the destruction of our manufacturing capacities.

Just like immigration, there’s a broader globalists vs nationalist divide. Someone like Michael Lind would say there was an actual job loss or crisis among poor whites in the last few decades that also influenced the right's shift from libertarianism to economic leftism.

There's a horseshoe component to the whole thing: Tucker Carlson and Elizabeth Warren couldn’t be more opposed politically, but they have very similar economic policies. Bryan Caplan calls this bundle of far-left and far-right policies "statism”, or the idea that you can use the state to achieve a revolutionary (forward) or reactionary (backward) reset in human affairs.

Trade and economic growth

I think economic growth solves most wounds, and immigration and trade maximize economic growth. I am thus pro-immigration and pro unilateral free trade (pro meaning having no import barriers at all, no matter what other countries do, national security concerns being the exception which we’ll cover in a separate piece).

People often ask WTF happened in 1971 that caused rising inequality within America, thinking that the elites profited at expense of the masses, but what actually happened was that the wealth spread internationally. In 1981, 42% of the world was living poverty, by 2018, it was 8.1%.

Just like we did with immigration, let’s address the main critiques of trade.

Taking jobs again?

The first critique applies to both trade and immigration: Both take jobs from American workers, and reduce wages by introducing more labor supply.

How can people see the gains from trade/immigration if their job is outsourced or taken by an immigrant? The argument regarding cheaper goods or increased GDP feels abstract. What good is a cheap iPhone if you are unemployed?

Just like with immigration, the most immediate flaw in these arguments is the Lump of Labor fallacy. As we discussed:

Economies advance through the growth of market size on the demand side, and productivity growth on the supply side.

On the demand side, you want more and more customers to sell your stuff to, and you want them to be richer and richer so they can buy more of your stuff.

On the supply side, you want productivity growth, you want to make more stuff with less inputs, more revenue with lower costs, therefore higher margins, and more profit.

How do you get demand growth? First, you need more customers, so constraining immigration cuts the number of domestic customers, and constraining trade cuts the number of foreign customers

How do you get productivity growth? Through greater specialization and trade. This is Adam Smith's pin factory metaphor, which stated that:

“Ten workers could produce 48,000 pins per day if each of eighteen specialized tasks was assigned to particular workers. Average productivity: 4,800 pins per worker per day. But absent the division of labor, a worker would be lucky to produce even one pin per day….”

Again, if you constrain the number of people you trade with, you reduce specialization and trade, hence reducing productivity—another self-inflicted wound.

Think about the argument against automation: We don't want machines that take away the work that people do. Well, should we eliminate machines today that do work that people used to do? Should we get rid of tractors, and go back to plowing fields by hand? Would we really be better off?

See also Bastiat's metaphor of the "Candlemaker's Lament". The Candlemakers all team up to lobby for blocking the sun. Blacksmiths thought cars were a terrible idea — do we really want to still be riding horses?

The arguments against automation, against immigration, and against trade are all the same basic argument—the lump of labor fallacy.

The relationship between the market and trade

Now, to steelman another of the critiques, it is true that economic change can be and is dislocating to people who are in an existing industry, occupation, or geographic place. If you live in a town that has a car factory, and the car factory is shut down and nothing replaces it, that's a real problem.

But the misguided response of "that factory shouldn't have shut down and been moved to Mexico or China or robots or the cloud" inflicts real damage on the population you are trying to help.

How? Well, that factory shut down or moved due to economic reasons—or in other words there was a more cost-effective or higher-tech way to build the same product or some other product that renders this product unnecessary. So now you have to intervene in the market to keep that factory open there. That creates a deadweight loss in the economy because you are now pulling economic resources that could have been used more productively and using them to prop up something that the market no longer naturally supports.

Apply this across thousands of factories and thousands of towns and you can start to see the problem. All of the things that all of those factories make now cost more than they would if the market was allowed to work organically.

Cars are now more expensive and advancing slower technologically then they would have otherwise. The deadweight loss is causing other, newer, industries and products to not get made. It’s causing the economy to stagnate, and causing consumer prices for goods and services to rise, not fall.

To add insult to injury, the lower one's income, the more one spends on goods. A poor person spends a larger portion of their income on their car and their clothes and their food than a wealthy person.

And so if you, say, double the prices of all those things by your market intervention, which is not uncommon, you negatively affect that person's quality of life.

Meanwhile, higher-income people, including the entire upper middle-class policy and political apparatus that comes up with these ideas, doesn't experience that nearly as much, since they spend a lower percentage of their income on car and clothes and food.

Neither left-wing populists nor right-wing populists understand this.

Dominated by international trade?

Zooming out, People often overrate how much the US actually relies on trade. Total international imports are only something like 15% of US goods and services, and China is a fraction of that. But the point is that overwhelmingly our economy is still driven by domestic production, which makes sense. After all, we don't import our houses, our schools, our healthcare, etc.

Using international trade to try to address systemic issues around the middle class is highly unlikely to work even if it is a logically sound thing to do.

The economic logic in favor of free trade has been considered overwhelmingly obvious for 200+ years. To economists, arguing against free trade (for economic reasons, not military reasons) is a lot like arguing the world is flat.

This was a huge debate in the 1980s and 1990s as well, except then the bogeyman was Japan, and later Korea. "Competitiveness" was the buzzword of the time for this topic, the idea being that we need to "compete and win" vs Japan or they would "compete and win" vs us.

Kling typically argues that when people attack immigration or trade, what they are really unhappy with is the shifting composition of the underlying economy. And they can't hold back the shifting composition of the underlying economy, since that's the result of actual technological and methodological progress that is resulting in shifting consumer wants and needs. Instead they go after the foreigners

Peter Thiel has an argument about innovation being vertical 0-1 progress and globalization/trade being horizontal (just copying), the latter of which is antithetical to innovation. Peter thinks he's outsmarting the economists. Maybe he is. Peter often has a simple theory.

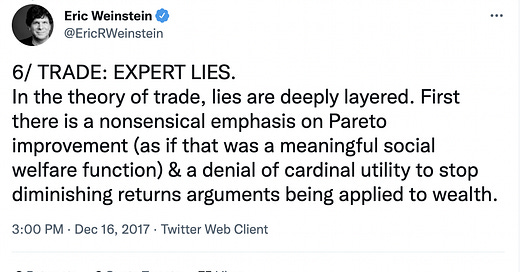

Contra Peter, Eric Weinstein has highly complex contrarian theories on immigration and trade. :

This is one of those topics where it's like, OK, maybe you've developed a new theory of trade that overturns 300 years of economic thought and 200 years of professional consensus across nearly the entire political spectrum. Maybe. But it’s more likely than not that these notions of cutting trade might hurt the very people you’re trying to help, for a few reasons:

Many goods and services become more expensive, but especially goods. Lower-income people spend a higher percentage of their income on goods.

Many inputs into *American-made* goods and services become more expensive, making American export industries less competitive and hurting jobs and wages in those industries.

Retaliatory trade barriers from foreign partners damage American export industries and hurt jobs and wages in those industries.

The US economy therefore becomes smaller with more expensive goods and services and with lower jobs and wages. You hurt the people you were claiming to want to help.

Maybe ordinary American workers can't be expected to understand Econ 102, but policymakers ought to.

Back to our original question about Apple:

“How can people see the gains from trade/immigration if their job is outsourced or taken by an immigrant? The argument regarding cheaper goods or increased GDP feels abstract. What good is a cheap iPhone if you are unemployed?”

Put differently, would Apple be serving America’s interests better by building in America? Well, this argument has a reductionist view of what "Apple" is. Apple is its shareholders and employees, but it is many other things as well. It's an entire ecosystem of goods and services around its products, most of which it doesn't own. It's all of the productivity benefits that customers of its products get, including many millions of small businesses. It's all of the spillover economic growth and job creation in the communities in which it operates. It's all of the training that it gives its employees and members of its ecosystem which grow human capital. It’s so much more.

Apple benefits far more people than GM or GE ever did.

Trade and increased immigration clearly benefit us as a society, but detractors will still bring up non-economic objections like national cohesion. Open borders enthusiasts like Matt Yglesias and Bryan Caplan just handwave away or ignore these kinds of concerns.

It’s reasonable to want the people who are neither super high IQ nor super mobile to still able to have pride in their towns and communities and work as opposed to just being cogs in the capitalist machine, or so the logic goes. It should be OK for people who want to live in the same town their whole life, have a 9-5 job, be able to have a house and a family with just a high school education, have the same job for 40 years, and not have to move away from family, friends and church etc. to get a new job—but there’s a question of how much prosperity we’re open to sacrificing to get it.

Conclusion

In summary, here’s the case for trade: As we said in growing the startup economy: “You can either increase the inputs, or you can increase the efficiency by which the inputs collaborate with each other.”

Trade is the efficiency by which the inputs collaborate with each other. Innovation emerges from the remixing of ideas. It is, as the name of Matt Ridley’s book suggests, “Where Ideas Have Sex”. So more trade means more productivity. And more productivity means more growth.

Agree, I’m a big fan of Thiels work - but he’s not outsmarting economists on trade or monopoly.

I think for the 1971 piece overregulation is underrated as a factor, there are very specific bottlenecks in each industry. I debated with Tabarrok on that point pushing back against his Baumol Effect piece and he didn’t push back much: https://open.spotify.com/episode/472XmRU4HiHNvJwjvaSxFk?si=g8r9akiuQLq9aJ4msCgf7w

Great article, if only people understood intuitively the benefits of trade!

"Manufacturing abroad, for example, can allow workers in the U.S. to focus on higher value-added tasks such as research and development, marketing, and general management. Additionally, expanding overseas to serve foreign customers or save costs often helps the overall company grow, resulting in more U.S. hiring."

https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-exporting-jobs-canard-1497482039

I think that one thing is missing from the national conversation is that we don't have globalization or protectionism. But rather we have regionalization. Shannon O Neil wrote about this in "The Globalization Myth, Why Regions Matter". (You need to have her on in your podcast).

We basically have three regions that dominate 85% of global trade. North America, Europe, and East Asia(which includes south East Asia) export most of the world's goods.

Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, Russia & its former Central Asian proxies, and South Asia make up the the remaining 15%.

Also, 70% of European trade is within Europe. 50% of East Asian trade is within East Asia, and North America has 40% interregional trade.

For every Boeing (which is truly global in terms of its supply chains), there is many more of Chinese Great Wall Motors and German Audis. For Great Wall, the transmissions come from Japan, Chassis from South Korea, and bumpers from Taiwan. For German Audi, the power steering come from Sweden, water pumps from Italy, wheels from Czech Republic, and circuits from France. Now more regions are trying to make their own European Unions. Probably the one that's most successful is ASEAN, Association of South East Asian Nations which is going to be the alternative investment destination instead of Asia.

You can see more here (shameless plug):

https://yawboadu.substack.com/p/who-dominates-global-trade

https://yawboadu.substack.com/p/regionalization-in-global-trade